All photographs are by the author.

At first glance, it looked like a shattered prism of color, light and shadow tucked beneath the third floor overhang of MoMA’s grand atrium space. Ellsworth Kelly’s startling construction, Sculpture for a Large Wall was on display from April 30 through June 4 this year. Spanning nearly the entire length of the south wall, it could only be fully viewed end to end from the other side of the space, a view unfortunately compromised by a column standing about six feet out from the western end of the sculpture. Perversely, this encouraged me to walk around the column and look at the sculpture more closely. What I saw were two sets of four horizontal rows of thin metal rods set about a foot apart, hung from wall mounted supports at the topmost rod that push the entire assembly out about a foot from the wall. The sculpture started at approximately six feet from the floor and was easily 12’ in height. Metal panels of silver, yellow, blue, red and black—some rectangular, trapezoidal or curved on one side, similar in width and corresponding in height to the distance between horizontal rods—stagger across the expanse of the sculpture, seemingly moving back and forth, weaving in and out of the front and rear rods from top to bottom. The voids between the stacked panels form a rhythmic counterpoint to the colored panels. With the rods’ shadows on the wall behind, the overall effect was of a giant, metallic tapestry.

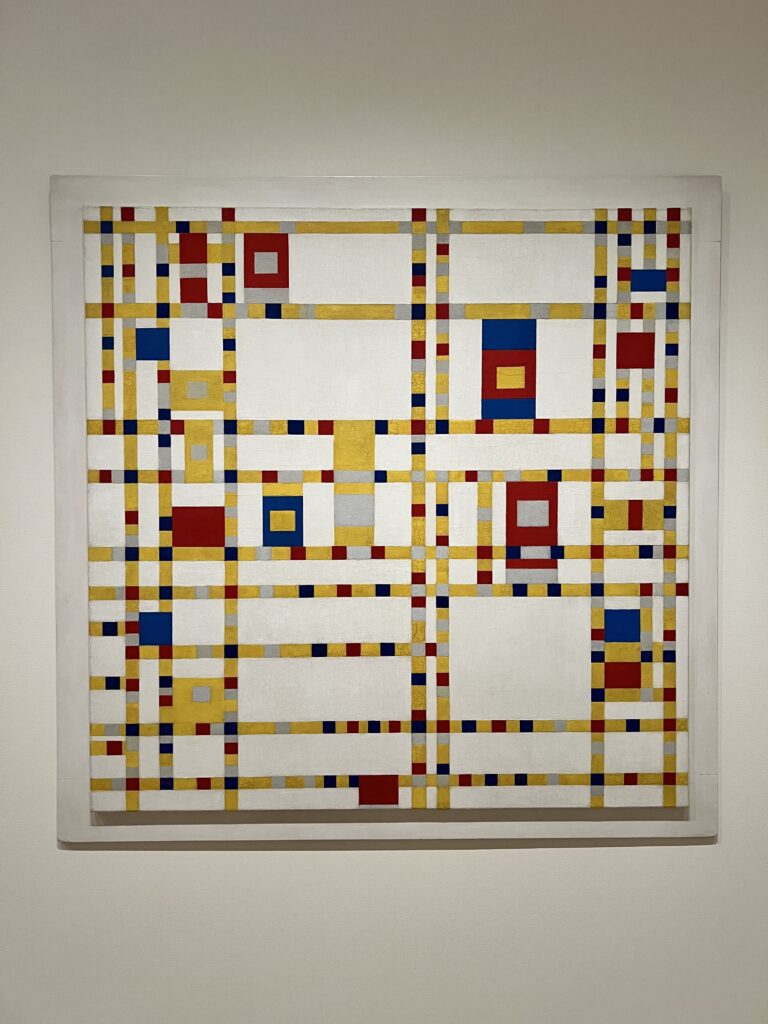

I immediately thought of Piet Mondrian’s painting, Broadway Boogie Woogie, his ode to New York City, although I wasn’t sure why. There was something about the use of color, the movement and the energy in the sculpture that reminded me of the painting. Kelly’s color palette is much cooler than Mondrian’s but for me they share a similar dynamism, albeit on much different scales. Curious, I decided to do some research to discover whether there was indeed any actual connection between Kelly and Mondrian or whether I was looking at these pieces through my own bias. Mondrian and De Stijl, and the related art and architecture movements around that era, have always fascinated me.

Kelly moved to France in 1944 after completing his studies in Boston at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. In Boston, and later in France, Kelly became fascinated with the idea of the wall “as an outdoor art of spectacle.” His early works imply an architectural setting, and the metaphorical wall became the starting point for this work. [1] While in France, Kelly was greatly influenced by Le Corbusier. He visited Corbusier’s Habitation apartment house in Marseilles, and had studied his Swiss Pavilion at Cite Universite in Paris. Le Corbusier and Kelly never met but through a mutual connection, Le Corbusier was shown slides of some of Kelly’s paintings. Kelly’s work prompted Le Corbusier to comment that “this kind of painting needs the new architecture to go with it.” [2] It was Le Corbusier who argued that the new modern architecture of “regular, modular facades, bare walls and free plan” required the application of color to give meaning, reminiscent of the stand taken by Theo van Doesburg and Gerrit Rietveld, two of the founders of the De Stijl movement.[3]

Serendipitously, Kelly met Michel Seuphor in late 1949. Seuphor was an artist, critic, champion of Mondrian and co-founder of the Cercle et Carre (“Circle and Square”) group. He was also an historian of the De Stijl movement. Like De Stijl, Cercle et Carre was founded around the idea of an aesthetic union between art and architecture known as Neo-Plasticism. So clearly, Kelly was immersed at a pivotal point in his career in all of the swirling theories and movements in Paris at that time.

Sculpture for a Large Wall was commissioned in 1956 for the lobby of Philadelphia’s Transportation Building, centerpiece of the new Penn Center and designed by Vincent Kling. It was Kelly’s first substantial undertaking and it marked a turning point in his career. The idea of the wall as public art that was nurtured in France, “an art for the city,” gave way to the reality of the American notion of art as a commodity, suitable for viewing in a gallery or a museum. [4] Yet, Kelly didn’t lose sight of his belief in the interconnectedness between art and architecture. The sculpture’s precursors were wall mounted studies that he did in the early 1950s still exploring the relationship of the canvas to the wall:

“I began to think of the works as architecture and wanted them to be gigantic walls.”[5]

In an unpublished statement from 1957, concurrent with the installation of Sculpture for a Large Wall, Kelly cited the virtue of Constructivism (a precursor to De Stijl) in what was practically an echo of Le Corbusier:

“Today there is very little collaboration of the plastic arts with architecture producing anything of real value. Perhaps the reason for this is that most contemporary painting is too personal for large wall spaces and the easel painting artist is more involved in his painting as an end in itself…However, there is an awakening among some artists to the demands made upon them by the new architecture. This movement in painting is called Constructivism; an art using pure colors expressed in simple monumental forms lends itself easily to modern building. The glass and steel reinforced concrete structures have created a new form and a new space to work upon. The monochrome buildings demand color, and the spaces demand an image on a large scale…”[6]

Kelly’s original intent for the sculpture’s metal panels was to use primary colors, an approach with precedent in the work of Piet Mondrian and De Stijl. The use of a grid—looser and elongated in Sculpture for a Large Wall, an evolution of the more rigid grid system in Kelly’s earlier works—could well have been influenced by Mondrian’s grid paintings such as Broadway Boogie Woogie. [7]

However, whatever aesthetic influences Kelly absorbed from his time in France were purely formal. “Despite his growing admiration for Mondrian, and even the occasional similarity of some of his own work to that of the Dutch master, he could never give himself over to speculation in pure form.”[8] The association with Neo-Plasticism was superficial and inaccurate.[9] The more muted colors in Sculpture for a Large Wall were actually an accident of fabrication. The panels were made from anodized aluminum, a new process for that time, and Kelly was unable to achieve the colors he wanted.[10]

In 1998, with the Transportation Building facing major renovation work, the sculpture was removed and later reinstalled at the Matthew Marks Gallery in New York City. It was purchased that year by Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder and donated to MoMA.

Yet, if the aesthetic qualities between Kelly’s Sculpture for a Large Wall and Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie are tenuous, each in its own way manipulates negative and positive space using color, shape and line. This is undoubtedly what I reacted to. Ironically, it is the larger sculpture that operates on a human scale of wall and volume, while the small painting requires the mind’s eye to “see” beyond the constraints of the canvas, and even the museum itself. Sculpture for a Large Wall is a tactile experience; Broadway Boogie Woogie is an experience of imagination. Using similar aesthetic tools, both ask the observer to consider their place in the built world.

Sculpture for a Large Wall is also a reminder that what was old can be new again—the shock of discovering that a 66-year old construction by an artist fascinated with architecture, mounted in a contemporary space, can get us to think about space, form, scale, volume, color and movement—all of those qualities intrinsic to great buildings.