All photographs are by the author.

Are there better alternatives to the large scale urban planning long associated with cities like New York? That’s the question the curators of the new Architecture Now exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) have asked themselves. This inaugural show, intended to “highlight emerging talent and foreground groundbreaking projects in contemporary architecture” in the New York City area, never clearly answers this question. “In contrast to the violent and disruptive nature of large-scale infrastructure and urban renewal initiatives“ twelve projects were selected that “propose subtler, nimbler interventions.” These are projects that “critically engage with their material and social contexts to propose ways in which architecture can serve as a public amenity.” They “reimagine the uses of civic infrastructure, redistribute private resources, and mine the potential of emerging technologies.” These lofty goals belie a lack of clarity in the exhibition that starts with the very wording the curators use in the title and in the introduction.

New York, New Publics is the exhibition’s name. Using the word “public” in the plural form is unusual, and it’s the first thing the visitor notices when entering the third floor Philip Johnson Galleries. Once they’ve entered the galleries, the visitor encounters the exhibition’s introduction on the rear wall that expands on the statements quoted above. The visitor learns that each project is accompanied by a video that “provide[s] a glimpse into the daily uses of these architectures…” Seeing the word “architecture” used in this way is baffling. The visitor’s curiosity is piqued. Still unclear as to what the curators mean by “publics” and “architectures,” the visitor starts walking through the galleries, hoping that the exhibits will collectively yield an answer. [1]

The exhibition has been laid out to mimic the experience of randomly walking through a city neighborhood so there is no set way to view the projects. Most visitors seem to walk counter-clockwise, perhaps drawn first by the glass wall overlooking MoMA’s Sculpture Garden that forms the entire east wall of the galleries. This offers the visitor a spectacular view not only of the Garden but much of midtown beyond. It is distracting, in a good way, a short story of Manhattan’s architectural history told in a single glance. It’s a fitting backdrop.

Here the visitor really notices the first exhibit. The curators have hung a colorful glass panel approximately eight feet high by 12 feet long several feet in front of the glass wall, taking advantage of the daylighting it provides.

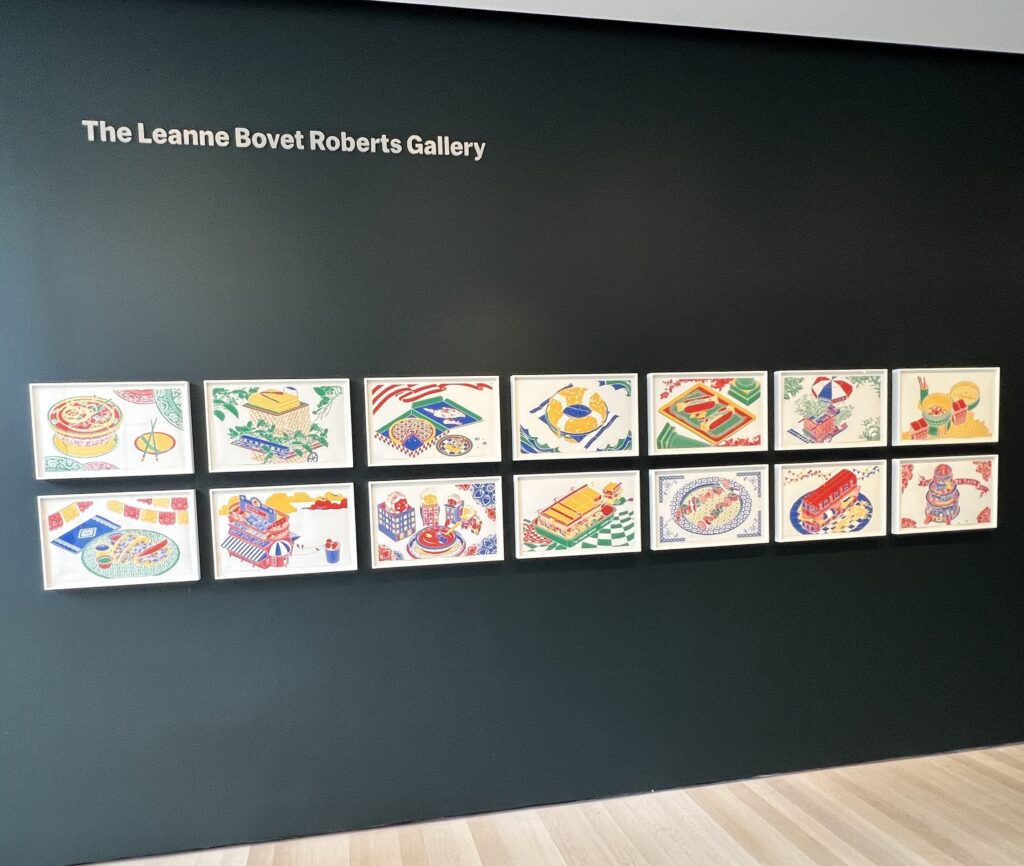

The translucent glass panel was made by architect/artist Olalekan Jeyifous. It is similar to the 28 that he designed for the 8th Avenue Subway Station in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, commissioned by the Metropolitan Transit Authority. 14 rectangular drawings, studies for the glass panels that were installed in the subway station, are mounted at eye height on the adjacent wall. They are playful, almost circus-like in their depiction of Sunset Park neighborhood touchstones. The video that accompanies this exhibit (similar to the video that accompanies each exhibit) provides more information about the actual process. Clearly these panels greatly enliven the experience of traversing the subway platforms. However, the Metropolitan Transit Authority has commissioned significant artwork for numerous subway stations. There is nothing in this installation that explains why this station was chosen by the curators over others. Perhaps it’s the most recent or the most neighborhood centric?

On a shallow, black platform in the middle of this end of the galleries sit three fake, black fire hydrants with spindly blue appendages—prototypes for providing potable water for outdoor recreational use and wildlife, and to reduce the use of plastic water bottles. The exhibit was developed from a student workshop led by Agency-Agency and Chris Woeboken Studio. They’re playful and the real world applications shown in the video are convincing. However, the visitor is left wondering how such a project could be implemented knowing that fire hydrants are a kind of public utility.

Nearby, a large photographic montage on the far north wall shows an image of General Toussaint Louverture that easily rises 10 stories at Columbus Circle in place of the existing Christopher Columbus statue. It’s an example of an augmented technology project utilizing the camera common to every cell phone. Developed by Kinfolk, a Brooklyn educational non-profit, on-site iPads allow the visitor to “see” smaller, similar projections at two tree-like pedestals placed close-by. This is perhaps what the curators referred to as “the potential of emerging technologies.” While the exhibit is thought-provoking and fun to play with, the way that this technology can usefully challenge our ideas of urban spaces remains otherwise unexplored.

These three exhibits are indicative of a handful of other ones chosen by the curators—unique, experiential, small-scale with a limited echo. They are certainly notable but has their significance been magnified by the imprimatur of MoMA? Three larger projects that the visitor next encounters are better able to stand on their own.

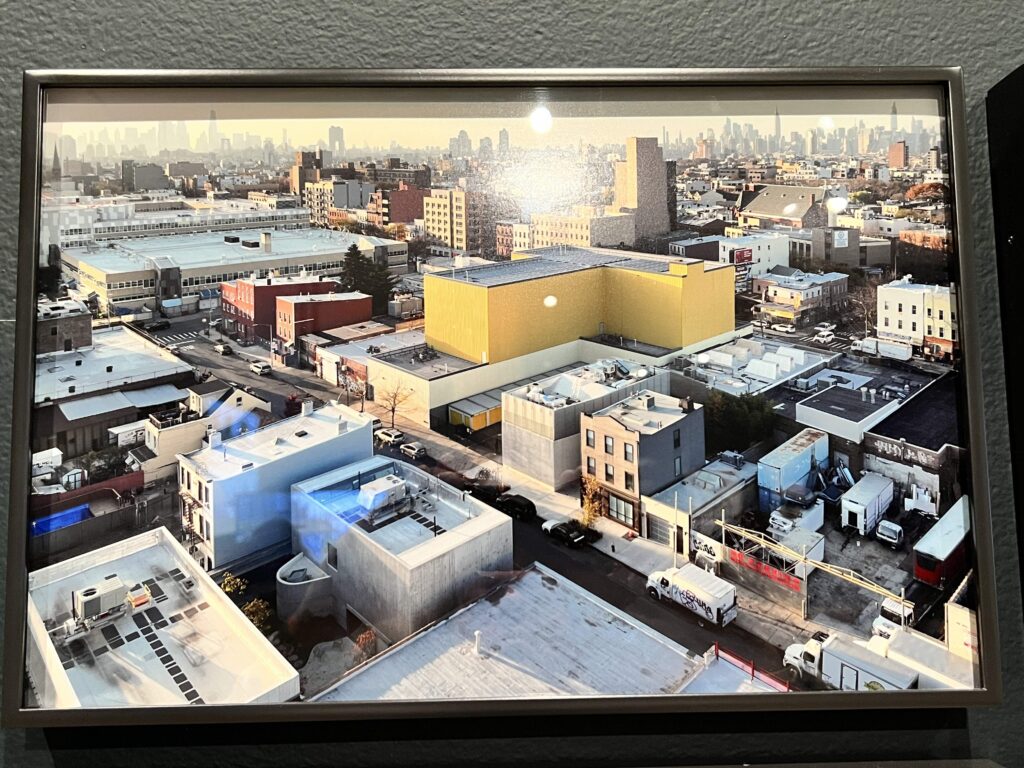

In a Bushwick neighborhood of small-scale residential and warehouse buildings, the architecture firm SO—IL has woven two pairs of small buildings across the street from each other for the non-profit cultural organization, Amant. Green pockets between each pair, co-designed with Future Green Studio, provide an outdoor release for the largely windowless gallery and performance spaces within each building. The creative use of faceted brick cladding, smooth and striated concrete, metal panels and the neutral palette of all of the building materials creates a distinct identity for Amant and a low-key backdrop for the varied streetscape. (Picture) There’s no question that these buildings “fit” in the neighborhood. If this is MoMA’s answer to “the disruptive nature of…urban renewal initiatives…of the past century,” then championing a contemporary approach to urban planning that architectural historians (and architects of a certain age) will remember as “collage city” is certainly worthy.[2]

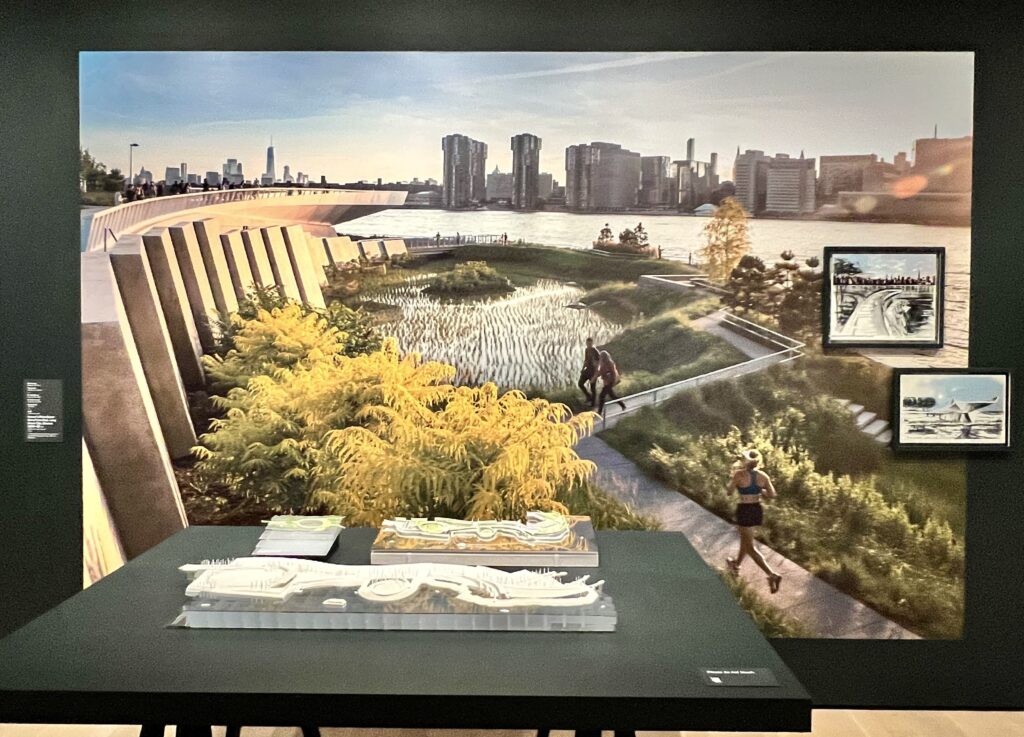

Continuing to move counter-clockwise through the galleries, the visitor next encounters the Hunter’s Point South Waterfront Park exhibit. Constructed along the East River in Long Island City, Queens, the park includes playgrounds, a bike path, terraces, lawns and promenades—all offering spectacular views of Manhattan’s east side. The environmentally resilient design was a collaboration between landscape architecture firm SWA/Balsley, architecture firm Weiss/Manfredi and engineering firm, ARUP. The park spans 30 acres and it’s impact as a model for developing under-utilized areas of New York City’s waterfront is citywide. Locally, it’s a welcome relief to the theme park of high-rise residential towers that has transformed this part of Long Island City into an energetic but visually sterile neighborhood.

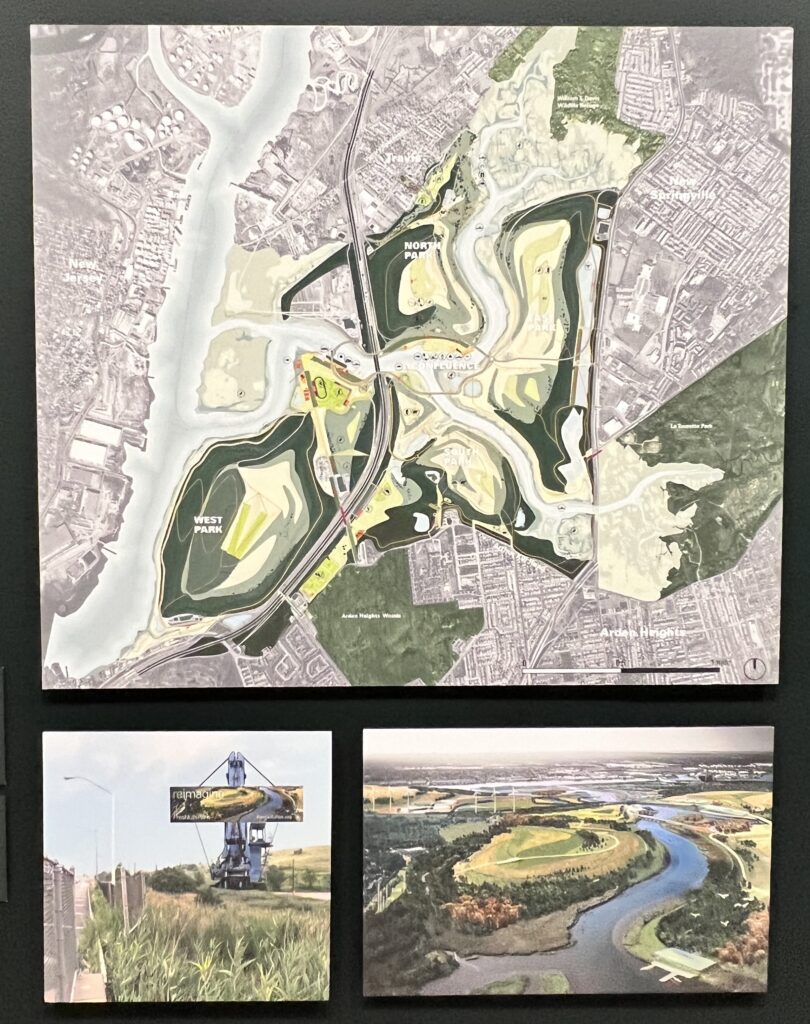

On the west wall is the exhibit showcasing the massive makeover of New York City’s former landfill on Staten Island, Freshkills, into a park that will be much larger than Central Park at completion. It is a remarkable project that turns what was an enormous blight on Staten Island of 150 million tons of waste into a 2,200 acre resource for local residents of ball fields, hiking trails, playgrounds, wetlands and nature sanctuaries. James Corner Field Operations, a landscape architecture and urban planning firm, was awarded the project in 2001. Reclamation is about halfway complete. While this site is unique in New York City, this approach has national ramifications. New York City has moved its garbage elsewhere and created a kind of green oasis for Staten Island but at what impact to these other communities?[3] This is not addressed in the exhibit.

Hunter’s Point and Freshkills Park are both publicly owned land. Reflecting on the exhibition’s introduction, the visitor notes that these two NYC driven projects certainly represent “subtler, restorative interventions.” However, the visitor laments the lack of any additional documentation from the curators about why these projects have been featured, particularly since both have already received national attention.[4] Was there more significant community involvement? Was there greater “political will”? Is there a model here that perhaps should have been followed for public/private initiatives like Hudson Yards?

Of minor note as the visitor continues their walk through the galleries is the exhibit of the Public Member Spaces for the 1199SEIU Headquarters in midtown Manhattan by Adjaye Associates. This exhibit wraps around the wall that bisects the western portion of the galleries. Adjaye Associates enlarged significant historical photographs from the union’s archives and had them reproduced on wall mounted ceramic tiles surrounding these common spaces. A window in one area gives the passing pedestrian a glimpse of a vibrant mural inspired by a Frederick Douglas quote. The exhibit is described as an example of how “architecture can foster collective memory.” This is poorly worded. The idea here is more akin to the art that adorned many New York City building lobbies beginning in the 1930s such as the Diego Rivera mural that briefly occupied the 30 Rockefeller Center lobby, or the WPA murals that graced Harlem Hospital, Ellis Island and other notable buildings. Art in the public sphere is used to convey a larger message linking history, civics and memory.

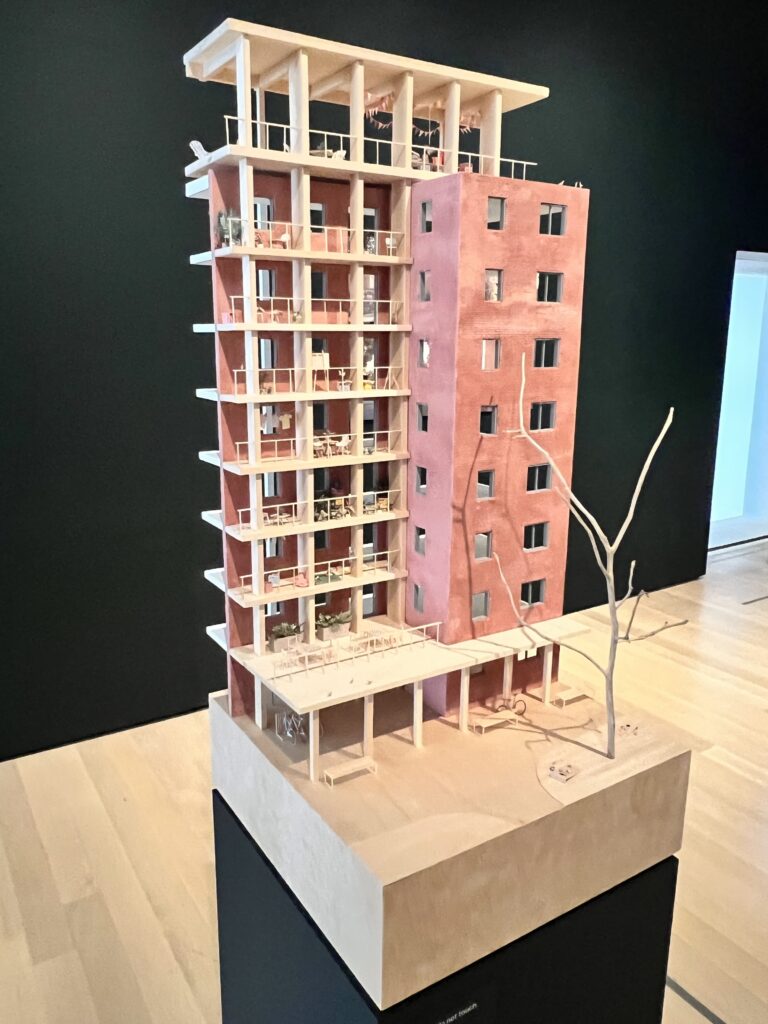

As the visitor circles now towards the south end of the exhibition, their eyes are drawn to a large architectural model. This is part of an exhibit called “Scalable Solutions for NYCHA” by Peterson Rich Office (PRO). The model demonstrates an ingenious way to add outdoor space to existing New York City Housing Authority apartment blocks. Wall mounted renderings and floor mounted site plans also illustrate the way in which additional public housing could be created by constructing new units at the corners of each block, utilizing a small portion of existing open space. In and by themselves, each design proposal seems feasible. Yet for anyone vaguely familiar with NYCHA’s budget woes, these seem like a pipe dream. The agency has acknowledged needing at least $40B to make existing repairs.[5] The exhibit description skirts this important issue, mentioning only that “Many of its complexes are in need of routine maintenance and costly repairs…” The visitor is a bit surprised that this project was included in the exhibition given the enormity of the problems facing NYCHA. If the construction of new blocks adjacent to the old ones is supposed to be part of the solution, then the visitor wants to know more. Perhaps public housing warrants its own exhibition since this is by no means a local problem.

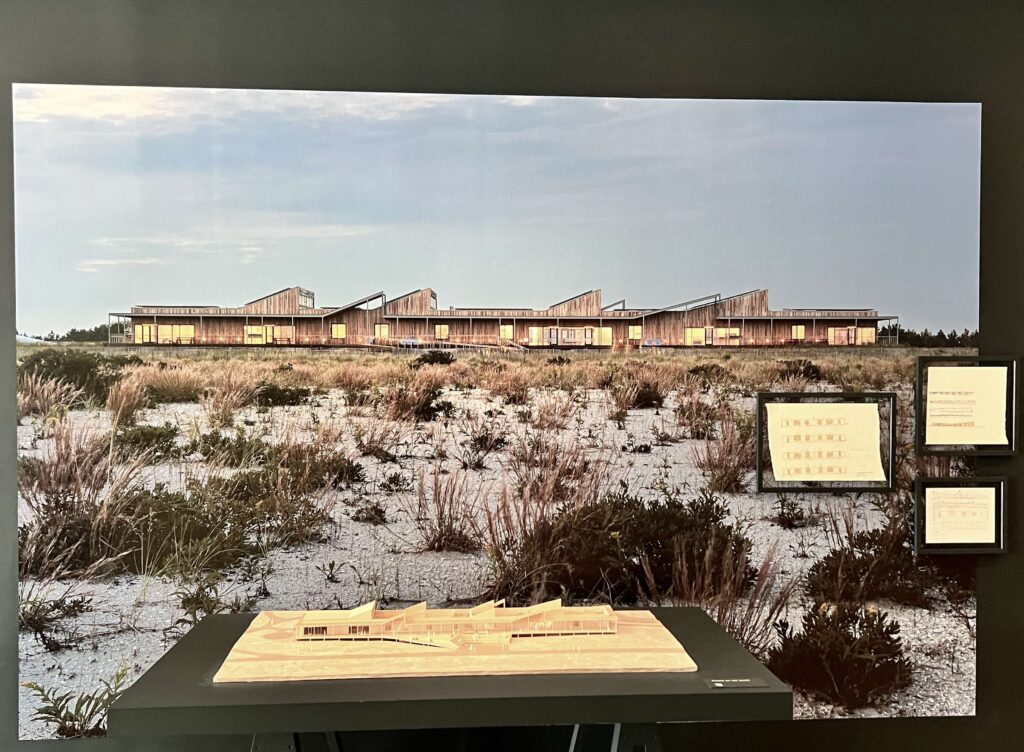

Exiting the galleries, the visitor passes by a model, photographs and sketches for the Jones Beach Energy and Nature Center completed in 2020 by nARCHITECTS. This is one of the few actual works of architecture chosen for the exhibition. The visitor learns from the exhibit description that the building was constructed on the site of an old parking lot. That explains the linearity and placement at the beach’s crest. It’s described as a “net-zero” building—still a rarity in the New York City area—achieved in part with geothermal wells and solar panels. If this is one of the reasons the project was chosen for the exhibition, the visitor wishes there was more description of the engineering design needed to achieve this.

The visitor leaves the exhibition with no better idea of what the curators meant by “publics” and “architectures,” and critically, little idea of why some of these projects were chosen at all. The overly broad claims in the exhibition’s introduction have largely gone unproven. There is a deficit of rigor in the selection of projects that is rooted in the language the curators used to convey their vision. The projects have little in common other than they sit in the same room; few can actually be described as “architecture.” It’s a very high standard that the curators are holding themselves to when they declare that Architecture Now will “serve as a platform to highlight emerging talent and foreground groundbreaking projects in contemporary architecture.” It’s a standard that this inaugural exhibition has not met.

[1] A reference to “publics” and “architectures” can be found online through the Oxford Languages dictionary used by Google; each word is defined only as a plural noun of the root word. No other meaning or usage is provided. Oxford Reference, the digitized compendium of all of Oxford University Press’s Dictionaries, Companions and Encyclopedias does define “publics” as a “loose, transitory and heterogeneous social collective (not normally termed ‘groups’) unified by shared interest in particular events or issues…” It does not provide a reference for “architectures.”

[2] Fred Kotter and Colin Rowe, Collage City (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 1979). As described by the publisher, “This book is a critical reappraisal of the contemporary theories of urban planning and design and of the role of the architect-planner in an urban context. The authors, rejecting the grand utopian visions of ‘total planning’ and ‘total design,’ propose instead a “collage city” which can accommodate a whole range of utopias in miniature.”

[3] New York City’s garbage is sent to waste-to-energy and landfill facilities as far away as 600 miles from the city. See the video and transcript at: https://www.businessinsider.com/what-happens-to-new-york-city-trash-2021-3

[4] Hunter’s Point won the 2019 American Society of Landscape Architects Honor Award for General Design and the 2020 American Institute of Architects Regional and Urban Design Award. Freshkills Park won the 2010 Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum’s Design Award.

[5] Russ, Gregory. “NYCHA head: Agency now needs $40B in repairs.” The Real Deal, January 14, 2020. https://therealdeal.com/new-york/2020/01/14/nycha-head-agency-now-needs-40b-in-repairs/